February 3, 2026

The FCC Ban is Forcing the U.S. Drone Market to Grow Up

Author

Accelerating a transition that was already underway.

The FCC’s recent action on new foreign-made drones and components has been widely described as disruptive. That’s true.

But from an investor lens, the more important point is this: it accelerates a transition that was already underway. And, makes the path forward clearer.

The U.S. commercial drone industry is being forced to decide what it wants to become.

The question investors should ask

The question is not whether demand exists. Commercial demand is already real: agriculture, utilities, infrastructure, public safety, environmental monitoring.

The question is whether the U.S. market grows as:

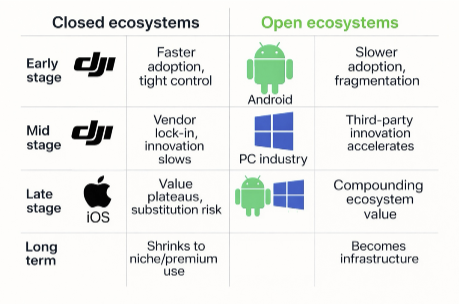

- a fragile set of closed stacks that require enormous capital and ongoing support expense to replicate and manage end-to-end, or

- a durable ecosystem where specialized companies build at the right layers and compound innovation downstream.

Those two outcomes produce very different investment dynamics.

Why “everyone must be Apple” is an expensive bet

Many investors naturally gravitate toward vertical integration. It feels defensible: own the hardware, own the software, control the whole experience.

In practice, that's the most expensive way to build a market.

When every manufacturer believes they must recreate the entire stack — aircraft, components, compute, software, data, compliance, workflows — the industry duplicates massive R&D effort. Timelines slip. Prices rise. Adoption slows. The end user loses.

This is especially acute in commercial drones because affordability matters. Drones are tools. Farmers, utility crews, inspectors, and first responders buy drones because they reduc risk, saves time, and integrate with the rest of their work.

An industry that requires every OEM to become a fully integrated software company will produce fewer viable manufacturers and higher prices for operators.

Why drones behave more like computers than autonomous mobile robots

A common argument against an “ecosystem model” is that robots require highly customized software, tightly matched to hardware. That is true in many robotics categories.

Commercial drones are different.

Drones are closer to standardized platforms with payload variation and workflow variation. The airframe and payload matter, but the operational workflows matter just as much: job planning, compliance, logging, maintenance, data management, reporting, integrations, and multi-site fleet operations.

That’s why the computer analogy keeps coming up.

Computing scaled when specialized companies competed at the right layers — components, hardware assembly, operating systems, applications. That ecosystem produced many winners and ultimately built the market faster than any single vertically integrated approach could have.

The same basic logic applies here.

Where the government focus helps, and where it doesn’t

The U.S. government is clearly pushing to build domestic supply chains, primarily through defense initiatives. That can be a jumpstart for components and manufacturing.

But commercial drone operations have fundamentally different requirements than the “attritable” systems currently being sourced by these government initiatives.

Commercial operators need:

- durability

- reliability

- usability

- supportability

- repeatable workflows

- software that makes the drone a tool, not a project

A market that tells commercial users to “wait a few years” isn’t aligned with reality. Demand exists now, and the work will be done by whoever can serve operators with practical, repeatable systems.

So what’s the investable opportunity?

Open ecosystems aren’t “give it away for free.” They’re a different value-creation model. A durable U.S. drone ecosystem creates multiple points of value:

- aircraft manufacturers specialize in reliable performance

- component and sensor companies fill critical gaps

- software and data platforms become shared infrastructure that accelerates time-to-market

- operators benefit from choice, competitive pricing, and fast iteration

That structure doesn’t just create one winner. It creates a category with many winners — and a larger market.

Where American Autonomy fits

At American Autonomy, Inc., we’ve built for this environment: U.S.-built, secured, and hosted software that is interoperable and hardware-agnostic by design.

We believe core capabilities, including mission planning, data management, compliance infrastructure, operator workflows, can and should be shared across manufacturers. That reduces duplication, lowers costs, and allows OEMs to focus investment on aircraft performance and differentiated hardware.

The FCC’s action didn’t end innovation. It made the industry’s next chapter inevitable.

Now the question becomes: do we build an ecosystem that compounds, or closed stacks that fragment?

For investors looking at timing: this is a market that is shifting from possibility to structure. And structure is where durable value gets created.